Grande, R. (2012).

The Distance Between Us; A memoir. New York:NY, Washington Square Press.

Book 2: Chpts 1 – 12

After a harrowing trip across the border to El Otro Lado,

Mago, Carlos and Reyna began a new life in their new country as a new family.

Their father and Mila owned a fourplex in Los Angeles and they crowded in one

of the smaller units but were together. All but one: Juana refused to give

Natalio Betty’s birth certificate and unfortunately, she was left behind in

Mexico with her mother.

Life was different in Los Angeles. The siblings had access

to television unlike they had in Mexico but the kids did not play on the

streets and the mothers did not sit outside gossiping with their friends. Reyna felt conflicted, but the possibility of

being away from Mago and the opportunity to have a better education kept her

hopes rooted in America.

The first day of school as a fifth grader was a life

changing experience for Reyna. Imagine entering a world where you do not

understand the language and not everyone can understand you. The night before,

Natalio threatened his children with sending them back to Mexico if they

brought home anything less than perfect grades so the stress, both internally

and externally, was immense. He told

them the reason he brought them to America “to get an education and to take

advantage of all the opportunities this country has to offer” (p. 166).

Reyna’s first American classroom experience was pure disruption

and distraction. Her teacher was Mrs. Anderson, and she spoke a little Spanish,

but she also had an ESL teacher, Mr. López. Within minutes of being there, her

whole identity is challenged as Mr. López tells her that she can only use one

of her last names because “That is the way things are done in this country” (p.

172). She goes from Reyna Grande Rodriguez to Reyna Grande and the part of her

identity that comes from her mother is erased.

During class, Mr. López starts to teach her, and a few other

non-English speaking students the alphabet.

They sit at a table in a corner doing their instruction at the same time

as the rest of the class. They are not allowed to speak loudly for fear of

distracting the rest of the class, but what about them? The stress she has put

on herself is so great that even after the first day, when she was unable to

learn the entire alphabet in one day, she feels like she has disappointed him.

She feels like she owes him something and her way to pay him back “was to make

him proud of my accomplishments, because they would be his

accomplishments, too” (p. 173).

Mexico was the only home she’d ever known so it is not

surprising that even though she was in a place she had dreamed of, Reyna still

wished for home. She missed playing outside. Small things like pigeons resting

on a roof, a cup of hot chocolate, and a whistling midnight train would remind

her of home. But she was determined to learn and determined to make her father

proud.

Juana was not always a good mother, and although their

relationship was conflicted, Reyna loved her, as would most children. Her

stepmother, Mila, was a steady presence in her life and did a decent job taking

care of the three children that had been unexpectedly thrust upon her. But

their relationship was conflicted too. Once Reyna called her “Mamá Mila” when

coming out of anesthesia and Mila corrected her and told her to just call her

Mila. Ouch! But Mila may have her own reason’s for not wanting to get close to

the children. Mila was an enigma to them and over time they find out that

behind her pretty clothes there is a sad tale. When Mila met their father, she

was also married and had three children of her own. Her family shunned her for

leaving her husband and children for this new man. Her ex-husband grew tired of

the children and “dumped them at Mila’s mother’s house” (p. 180). Mila’s mother

fought for custody of Mila’s children, and won. However, Mila never gave up the

fight for her children which is different than Reyna’s perception of her own

mother’s fight for her.

When the children lived in Mexico, their father was a

mystery: “The man behind the glass.” Reyna and her siblings could affix any

ideals and traits upon him as they pleased and made him larger than life. The

man they currently lived with was also a mystery. They did not really know him and were a little

bit in awe of him sprinkled with a significant amount of fear. He definitely

did not know them.

Natalio did not allow for the children to do any wrong,

unfortunately, they did not always know what that was. Culturally, there were

so many differences and Reyna and her siblings had no reference. The children

were beaten for making a phone call and not knowing there was charge. Mago’s entrance

into womanhood was met with a beating due her father’s “beat now, no questions”

policy for missing school. The children regularly got spankings for offenses

they were unaware of. And while his punishments were harsh, he could be gentle.

When Reyna got lice again, she was terrified to tell him for fear of him

sending her back to Mexico. He responded gently and spent two hours delousing

and washing her hair. It was a memory she treasured.

Reyna was very observant. She watched her older siblings

navigate through middle and high school and the added complications of peers

and romance. She saw when her sister

became heartbroken over a boy who did not like her because she was a “wetback”.

Her brother also experienced heartbreak because he had crooked teeth and the girl

he liked, Maria, started a fight with Mago because Mago defended him when he

was caught staring at her. Mago wins the fight, but Reyna fears bad luck and is

cautious.

The juxtaposition of education and her father is a significant

factor to Reyna’s academic development. Reyna’s

father was only allowed to stay in school until he was 9 but he had a fire in his

heart for his children to be academically successful. He truly sees education

as an equalizer, as their way out of poverty and on to independence. He tells

them “School is the key to the future” (p. 227) and has high expectations for

them. All of these hopes and dreams for

them hum loudly through Reyna as she makes her academic progression. When she does not win a book writing contest,

she and the other ESL students are told by Mr. López that their books were

still good, but Reyna, under her breath, says “Just not good enough” (pg. 218).

The desire to make her father proud is

flamed and Reyna becomes determined to write a book that wouldn’t be rejected

and would make her father proud.

After he is mugged and then there is a shooting outside their

home and man is shot steps away from where Carlos had been playing, Natalio

becomes determined to learn English himself. He saw it as a way out: learn English

-- get a better job—move to a safer place. Reyna reflects on this as she says “my

father’s desire for a better life was palpable. It was contagious. It was one

of the things I most respected about him” (p. 237).

Mila and Natalio got married at some point in 1987 and he

began to work on green cards for himself and the children (Mila was already a naturalized

citizen). President Reagan had approved an amnesty program in Nov. 1986 and Natalio

saw this as way for them to “stop living in the shadows” (p. 229).

There hopes were nearly dashed when Natalio went to Mexico after

learning about his sister, Tia Emperatriz, had stolen his dream house. While he

had lived on El Otro Lado for over a decade, he still dreamt of his house that

he had built. Tia Emperatriz finally got married but her husband was older and

poor. Natalio had allowed her to live in the house, to maintain it, but he did

not own the land and Emperatriz convinced their sick and frail mother to sign

over the deed to her. He is furious and attempts to get it back, but his dream

of returning to Mexico one day is dashed. When he returns to America, he is

broken and so are his dreams of making a better life for himself by learning

English.

In the middle of 1986 their father tells them that their mother

is not in Mexico, but in Los Angeles, living downtown. She has left Betty in

Mexico and now has a new baby “not three months old” (p. 220). Natalio is angry when they ask about going to

see her stating “Don’t you kids have any pride?” (p. 220). Although he tells

them she didn’t care about them, it’s their mother, and it is complicated.

Mago writes home and eventually learns through a letter that

Tia Guera and the now five-year-old Betty are coming in the summer. Ironically,

by bringing Betty, Guera would have to leave her own daughter, Lupita, which

only expands the cycle of leaving children behind.

It took some convincing, but Natalio eventually allows the

children to visit their mother, if only to see Betty. The children are

horrified by where their mother lives. Homeless people and winos line the

streets. Mago says “If I didn’t know any better, I would think we were back in

Mexico” (p. 222). They discover that

their new brother is named Leonardo and that Rey is the father. Rey is 15 years

younger than Juana and was only 21 when they first met.

The children confront Juana about not contacting them or

coming to see them but she explains that she wanted to give the kids “a chance

to get to know your father, and for him to know you, without me coming between

you” (p. 224). Reyna and her siblings understood what she was trying to say but

did not believe her. Reyna said it was the lowest point in their relationship

with their mother. They were not 2,000 miles away from her anymore, but the

emotional distance was just as far. Their mother did not “make space” for them

in her life, however she never stopped hoping that Juana would change.

Through this enlightenment, they began to see Mila more

positively. And while they were initially jealous of Betty and Leonardo getting

to eat junk and fast food, they appreciated Mila and their father later for not

allowing them to eat it when both Betty and Leonardo became extremely

overweight!

Mago was first person in their family to go to high school

and their father took her to buy clothes to celebrate. He could not buy Carlos

and Reyna anything because the lawyer fees from his divorce from Juana and

green card applications were expensive. Reyna did not understand this. She was

further distressed because as a third child, she would never be the first to do

much of anything. It made her determined to be the first at something –

something that would make her father proud.

Little did she know just a few days later she would be the

first at something: playing an instrument. She was placed into band and discovered

a new passion in music. She selected the Alto Sax. She liked playing music

because it didn’t require her to speak English, or Spanish. She didn’t need to

speak at all – “just play” (p. 232). Her father was excited for her. He had

wanted to be in the color guard when he was in the 6th grade but had

to quick school at age 9 to go work in the fields. He never got to play the

drums again. And worked ever since.

Reyna “played for myself and for my papi [sic], who never got another

chance to play anything” (p. 233).

There is so much in these chapters, about love and hope; rejection

and fear. Our parents want so much for us and we, even despite ourselves, want

to please them. Natalio is correct in thinking that education was their key to

freedom.

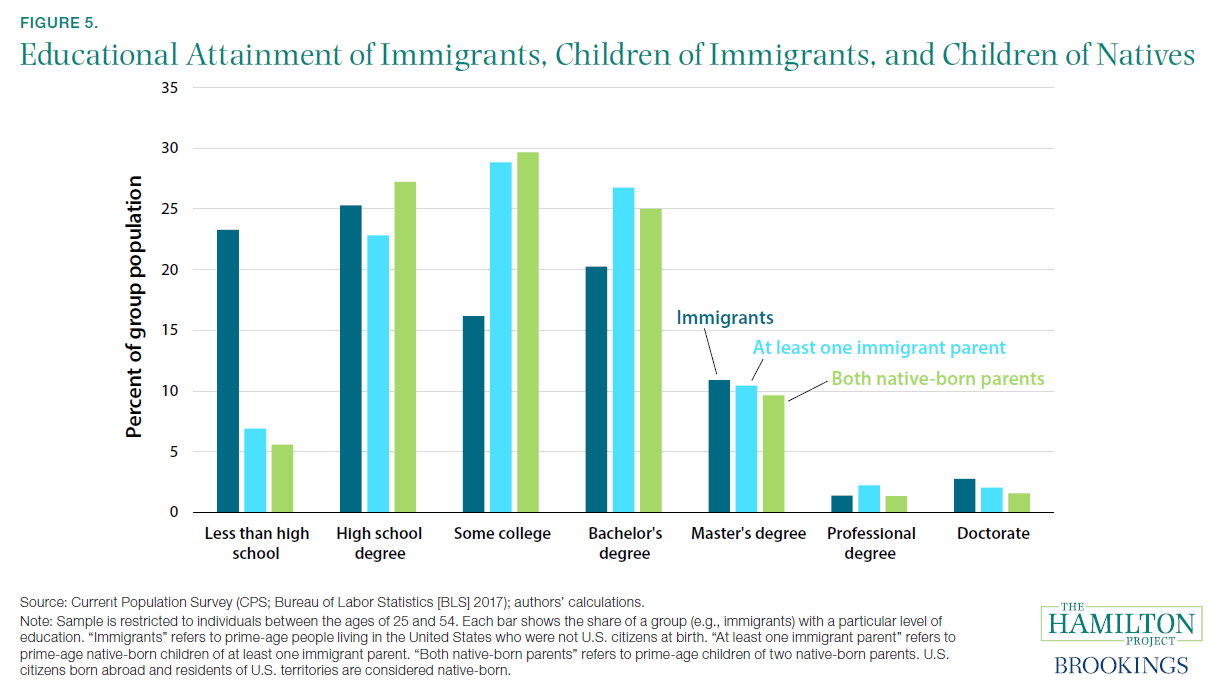

Below is a great graph of educational attainment of immigrants, children of immigrants and natural born children. Children of immigrants attain almost the same education level as natural born children.